Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

The greatest financial opportunities and risks do not lie in operational reports, but in the initial design, which determines up to 80% of a product’s total cost over its lifecycle.

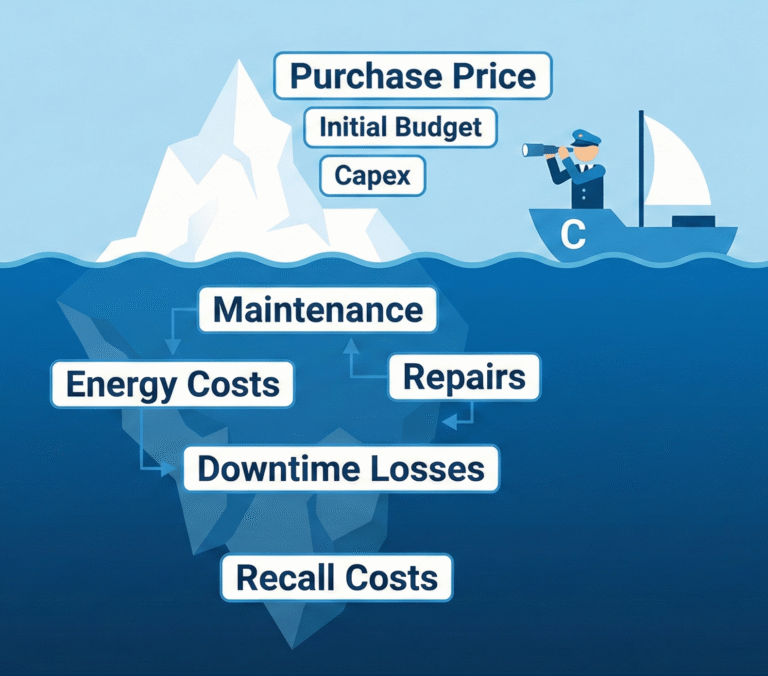

In my role as CFO, I see the same mistake in companies of all sizes: an excessive concentration on visible, current costs. It is like a ship captain seeing only the tip of the iceberg while ignoring the massive block of ice underwater that poses the real threat.

My job—and the job of any strategic financial leader—is to manage not only incurred costs (money that has already been spent) but, far more importantly, committed costs. These are the future obligations the company takes on due to decisions made in the early stages. And the fundamental business truth that is often ignored is that up to 80% of all future product costs are locked in during the design phase.

This is a principle I have been guided by throughout my career, and it differs radically from the classical view of finance.

The Trap of Short-Sighted Decisions: When Saving Today Creates Losses Tomorrow

The standard approach to procurement and capital investment is dangerously misleading. It encourages minimizing initial capital expenditures (Capex), often at the cost of a significant increase in future operational expenditures (Opex). The cheapest equipment today can turn into exorbitant electricity bills, frequent breakdowns, and expensive repairs tomorrow. This is not a saving; it is a deferred loss.

Business history is rife with tragic examples of what happens when this principle is ignored. These are not just engineering miscalculations—they are fundamental failures of financial strategy.

The Ford Pinto and Fatal Economics: When $11 Turns into Billions

In the early 1970s, as competition from Japanese automakers intensified, the Ford Motor Company introduced a new line of cars—the Ford Pinto. The Pinto was supposed to cost under $2,000.

During crash tests prior to the Pinto’s public release, it became obvious that the car had a dangerous structural flaw. The gas tank (Petrol tank – UK) was designed and positioned in such a way that in a rear-end collision at speeds of 20 mph or higher, the tank could rupture, causing a fire or explosion.

The cost of the fix? About $11 per car.

Instead, management conducted a cynical cost-benefit analysis, calculating that paying out compensation for projected deaths and injuries would be cheaper ($49.5 million) than fixing the defect in all cars ($137 million). This estimate assumed that each avoidable death would cost $200,000, each avoidable serious burn injury would cost $67,000, and the average repair cost for a rear-end accident would be $700. It was also assumed in this calculation that there would be 2,100 burned vehicles, 180 serious burn injuries, and 180 burn deaths.1

What did they fail to account for? A reputational catastrophe, multimillion-dollar punitive damages (in just one case, a jury initially awarded $125 million), the cost of a total recall, and a shameful place in business ethics textbooks. A short-term “saving” of $11 locked in billions in losses.2

The Boeing 737 MAX and Systemic Failure

A more recent example is the Boeing 737 MAX disaster. In a rush to compete with Airbus, Boeing decided not to develop a new aircraft but to modernize the old 737 platform. This short-term financial decision “locked in” the need for a complex software system, MCAS, to compensate for aerodynamic instability. Subsequent pressure to cut costs and timelines led to two plane crashes less than six months apart in 2018 and 2019. Experts agree that MCAS was both a flawed design and a symptom of broader structural issues at Boeing.3

The financial consequences were staggering: over $20 billion in direct costs and more than $60 billion in indirect costs due to lost orders and reputational damage.4

All of this is the result of an initial decision that prioritized savings on development while ignoring the massive risks locked in during the design phase.

The Digital Abyss: Underestimating TCO in Software and IT

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is much higher than the price of software. It is far more than meets the eye. TCO is the total cost of acquisition, use, management, and disposal of an asset over its entire lifecycle. The initial development cost often accounts for only 20-40% of the total lifecycle cost. The rest are committed costs for maintenance, support, integration, security updates, and technical debt.5

Case Study: The FBI Virtual Case File (VCF)

- The Promise: An ambitious project to modernize the FBI’s case management system with an initial budget of $170 million.

- The Reality: The project’s TCO skyrocketed due to poor project management and escalating unforeseen maintenance requirements.

- The Result: The project was scrapped after costs significantly exceeded the initial budget, and over $170 million of taxpayer money was wasted. This failure was a direct consequence of underestimating the massive committed costs inherent in complex, custom software development.6

These catastrophic failures are not “Black Swans.” They are predictable, logical consequences of a corporate culture and financial structure that prioritizes short-term, measurable cost savings over long-term, harder-to-quantify risk management.

The common thread is a failure of governance, where financial tools are used to justify, rather than challenge, strategically poor decisions.

- The Ford Pinto case shows how cost-benefit analysis, a standard financial tool, was grossly misapplied by excluding critical variables such as reputational risk and punitive damages.

- The Boeing case reveals a cultural shift from an engineering-centric to a finance-centric approach, where pressure on cost and schedule systematically outweighed safety and quality concerns. This created an environment where flawed decisions were not just possible, but probable.

The root of the problem lies not in a single bad decision, but in the systemic undervaluation of initial design, engineering, and quality assurance. When the CFO’s office and the executive team signal that the primary goal is to minimize initial capital expenditures (Capex), they inadvertently incentivize behavior throughout the organization that drastically raises the probability of catastrophic failure.

Designing for Success: The Power of Thoughtful Decisions

Dell Builds a Framework for Success

Custom computer assembly requires operators, time, and space. Dell was pleased that customers were enthusiastic about its products, but the company resisted the physical expansion of resources and staff that would be needed to meet growing orders.

Instead of adding floor space and people, the company chose a less costly path: it redesigned its products to make assembly and service easier and faster.

The Financial Result: The redesign saved approximately $15 million in direct labor costs. Crucially, the increased throughput allowed Dell to defer expensive facility relocation, saving millions more—a classic example of avoiding massive future incurred costs by making a smart decision at the design stage. 7

Thoughtful Design in Construction

Consider a real-world case of building an animal shelter in Yonkers. The initial power supply design proved unviable, and the utility company proposed a solution costing $150,000 that would take 9 months.

Instead of accepting these committed costs as a given, the contractor applied Value Engineering. He developed an alternative wiring scheme that required almost no work from the utility company.

The Result: Savings of over $100,000 and the facility launching 7 months early. 8

This is a perfect demonstration of my principle in action: investing time in analysis at the design stage avoided colossal future costs.

The Role of the CFO: From Bean Counter to Strategic Architect

This approach is what I consider the essence of the modern CFO role. It is not just about controlling money spent. It is about actively influencing decisions that determine how much we will spend in the future.

What does this mean in practice?

- Break down functional silos. The Finance Department must participate in design meetings from day one, working alongside engineers, designers, and operations.

- Change performance metrics. Procurement should not be evaluated by the lowest purchase price, but by the lowest Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

- Ask the right questions. “How much does it cost?” is an incomplete question. The right one is: “What is the total cost of this decision over the product’s entire lifecycle, including maintenance, energy consumption, repairs, and disposal?”

Shifting to lifecycle thinking is not an accounting exercise. It is a fundamental change in corporate culture. And the CFO must be its primary driver.

Because true financial leadership is not the art of cutting costs on the assembly line, but strategic foresight invested at the drawing board, where that invisible part of the financial iceberg hides.

Sources:

- The Case of the Ford Pinto, доступ отримано жовтня 24, 2025, https://www.cs.rice.edu/~vardi/comp601/case2.html ↩

- Ford Pinto Case | Kroot Law LLC, https://www.krootlaw.com/the-kroot-law-legal-information-library/articles/articles-on-personal-injury/ford-pinto-case/ ↩

- Did A Design Flaw Really Kill The Boeing 737 MAX? – Simple Flying, https://simpleflying.com/design-flaw-kill-boeing-737-max/ ↩

- Financial impact of the Boeing 737 MAX groundings – Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_impact_of_the_Boeing_737_MAX_groundings ↩

- The true cost equation: Software development and maintenance costs explained – IDEA LINK, https://idealink.tech/blog/software-development-maintenance-true-cost-equation ↩

- Total Cost of Ownership for Custom Software Projects: What … – Leobit, https://leobit.com/blog/total_cost_of_ownership_for_custom_software_development/ ↩

- DFMA Case Studies: DELL Builds a Framework for Success, https://www.dfma.com/resources/dell.asp ↩

- Value Engineering Case Studies – D&M Electrical Contracting Inc., https://dmelectrical.com/capabilities-value-engineering ↩