Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

What it is about

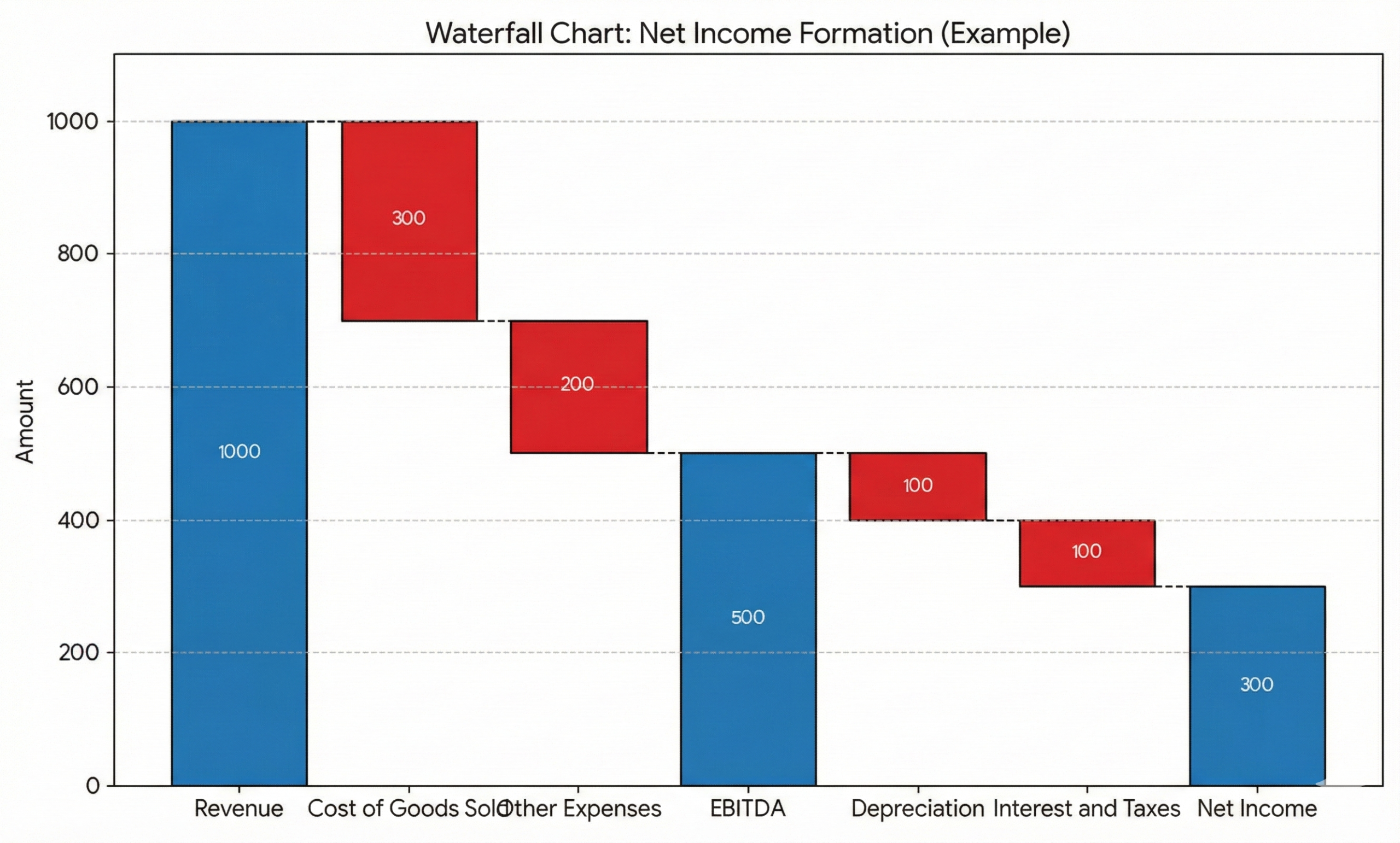

EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, and Amortization) is an analytical metric equal to earnings before the deduction of interest expenses, tax payments, and accrued depreciation and amortization.

Typically, analysts examine standardized metrics described in International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) or Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), as their calculation is clearly defined in the standards, making them comparable across enterprises and industries. However, there are metrics that do not belong to these standards but are widely used in practice. These are the so-called non-standardized financial measures. One of them is EBITDA.

International accounting and reporting standards (GAAP and IFRS) do not use this metric and do not contain a description of it. Although this indicator is not part of financial reporting standards, many companies publish it in their financial statements as additional information about the company’s activities.

Paragraph 8 of the first chapter of the IFRS Conceptual Framework indicates the possibility of presenting additional data in financial statements:

“…focusing on common information needs does not prevent the reporting entity from including additional information that is most useful to a particular subset of primary users.”

Why the EBITDA metric is used

Some analysts believe that this metric allows for a general assessment of a company’s ability to generate cash flow and is useful when comparing enterprises in the same industry with different capital structures.

Since financial expenses (interest) and income tax are excluded from the calculation of the company’s results, it is believed that this indicator characterizes the operational profitability of the company regardless of capital structure and jurisdiction.

Furthermore, by excluding depreciation from the calculation of financial results—which is considered a non-cash expense (since funds were spent on acquiring non-current assets earlier)—one obtains a proxy for the cash flow that the company is capable of generating through its activities, which can then be directed toward loan repayment.

This assumption may be correct, but only in specific cases and in the short term, when:

- the company’s non-current assets have been formed recently and do not require replacement or capital repair;

- there is no active business development and no expenses for acquiring new non-current assets.

For analysis, the Debt-to-EBITDA ratio or EBITDA margin is typically used.

Why EBITDA is misleading

1. Failure to meet expectations – it does not show the ability to generate cash flow (it disregards cash expenses for non-current assets in the current period and those already incurred)

In reality, expenses for the acquisition of non-current assets—that is, assets intended for use over more than one period—are actual expenses just like other operating costs. However, in the Profit and Loss statement, they are reflected in parts over the useful life of such a non-current asset (this is depreciation).

The enterprise incurs real costs (spends cash) on the acquisition of non-current assets, even before these assets begin to be used to generate income. These non-current assets wear out over time and require replacement. Thus, in the long term, assuming the company’s activity level remains constant and depreciation methods are chosen adequately, the sum of cash expenditures on non-current assets is approximately equal to the amount of accrued depreciation.

In the case of business expansion, the enterprise acquires new non-current assets. In such a scenario, cash expenditures on non-current assets (CAPEX) will significantly exceed the amount of accrued depreciation.

In active business operations, particularly in manufacturing, specific components of non-current assets—often expensive ones—wear out quickly and require replacement. According to accounting standards and established practice, such costs are generally recognized as capital investments and amortized gradually. However, in many cases, these costs are directly proportional to the volume of production output and are classified as variable costs when calculating production costs in management accounting.

One of the noted critics of using EBITDA for analysis is the renowned investor Warren Buffett, as he wrote in the 2002 Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report:

“Trumpeting EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization) is a particularly pernicious practice. Doing so implies that depreciation is not truly an expense, given that it is a “non-cash” charge. That’s nonsense. In truth, depreciation is a particularly unattractive expense because the cash outlay it represents is paid up front, before the asset acquired has delivered any benefits to the business. Imagine, if you will, that at the beginning of this year a company paid all of its employees for the next ten years of their service (in the way they would lay out cash for a fixed asset to be useful for ten years). In the following nine years, compensation would be a “non-cash” expense – a reduction of a prepaid compensation asset established this year. Would anyone care to argue that the recording of the expense in years two through ten would be simply a bookkeeping formality?”

EBITDA is an intermediate performance metric that allows one to examine a company’s efficiency “as if” it had no debt, no investment costs, no financial expenses, and no tax burden. Effectively, it attempts to assess the operational result of the business. However, this metric does not provide a complete picture of a company’s performance. For example, a company could ramp up debt financing almost indefinitely, which might lead to EBITDA remaining at an extremely high level, while net profit might be nonexistent because the majority of funds would have to be paid out to service the debt.

Although EBITDA can be useful for analyzing the operational efficiency of a specific company, it does not reflect net income, which may be too low for an investor.

2. The metric is absent from standards, and companies can manipulate its value

EBITDA is not part of Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). There is no generally accepted mandatory methodology for its calculation. Different companies use different methods to calculate it, which complicates the comparison of performance results across different companies.

For instance, some calculate this metric using only operating income as the revenue source. With this definition of profit, EBITDA is most closely tied to operating profit. At least theoretically, the exclusion of depreciation and amortization expenses is the only real difference between these two figures.

However, many companies interpret the name of this indicator literally, including all expenses and revenue sources, regardless of their connection to the core operating activity. According to this method, EBITDA is calculated starting from net income and adding back taxes, interest, revaluation amounts, and depreciation. This calculation formula allows for the inclusion of any additional income from investments or secondary operations, as well as one-off gains from asset sales, into the profit.

The EBITDA metric is advantageous for companies with high levels of capital expenditures (CAPEX), as it provides an opportunity to present their business to investors and creditors in a more attractive light.

Back in 2014, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) published a report on Non-GAAP Financial Measures.

IOSCO began its work on assessing non-standardised measures in 2002. IOSCO experts noted instances of inconsistent application of non-standardised measures and inadequate explanation of their meaning.

IOSCO outlines the requirements for reports containing non-standardised financial measures:

Non-standardised measures must be accompanied by effective information so as not to confuse or mislead investors. It is important that issuers ensure the transparency of non-GAAP financial measures and clearly disclose how such measures are calculated. Specifically, IOSCO requirements are as follows:

- Define each presented non-GAAP financial measure and provide a clear explanation of the basis of calculation.

- Non-GAAP financial measures should be clearly labelled in such a way that they are distinguished from GAAP measures. Labels must make sense and reflect the composition of the measure.

- Explain the reason for presenting the non-GAAP financial measure, including an explanation of why such information is useful to investors, and for what additional purposes, if any, management uses this measure.

- Explicitly state that the non-GAAP financial measure does not have a standardised meaning prescribed by GAAP for issuers, and therefore cannot be compared with similar measures presented by other issuers.

CFO Summary

A View from 2025: Evolution of the Approach

Rereading this article seven years later, I see that the fundamental principles remain unchanged. However, the experience of navigating through crises has taught me to be more cautious with the interpretation of cash flows. Today, I would add one critically important caveat regarding capital investments to this material. Below, I explain why high FCF is sometimes a harbinger of trouble rather than success.

EBITDA is a tool, not a panacea. I use it for a quick valuation of a business (via multipliers) or to compare competitors within an industry. But I never allow investment decisions to be made based solely on EBITDA, because it ignores the real need for reinvestment.

The Balance Between EBITDA and Reinvestment

However, Free Cash Flow itself can be misleading if a company artificially cuts capital expenditures. Therefore, my approach is: look at FCF, but strictly monitor the asset replacement ratio (Capex ÷ Depreciation). If FCF is high, but we are investing less than the depreciation charge – this is a warning signal, not success.

So, analyse the figures comprehensively. Business health is a balance between profitability today (EBITDA) and investments in tomorrow (Capex).

Pingback: Toxic KPIs: How Misguided Motivation Kills Your Business | Financial management