Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

Introduction: The End of the Era of “Intuitive Management”

For decades, Ukrainian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have functioned primarily on entrepreneurial intuition and the rapid reaction of their leaders. Intuition is the subconscious processing of familiar patterns. However, when reality has no historical precedent, intuition leads to cognitive biases, such as “survivorship bias” or the “illusion of control.”

Business owners, who often double as CEOs, have made decisions based on “market instinct” and empirical experience accumulated during previous crises (2008, 2014, COVID-19). They attempt to “adapt” situationally rather than building a system. But in current conditions, mere adaptation is insufficient. A structure is required – a risk map, action scenarios, and designated responsible persons. This is not bureaucracy; it is the minimum requirement to prevent production stoppages, customer loss, and unnecessary expenses.

Risk management is a tool for decision-making, not a blocker of initiative. It is about responsibility, flexibility, and antifragility. Having a basic risk management system is already a competitive advantage.

When you have a plan, you do not panic. You act.

This document is not an academic lecture. It is a practical guide synthesized from real experience in financial and operational management during crises. Its goal is to transform the fear of uncertainty into a structured decision-making system.

In the following sections, we will deconstruct the risk management process into component elements that are understandable and accessible for implementation.

Part 1. The Anatomy of Threats: Classification of Business Risks

Successful management begins with understanding the nature of phenomena. For a Chief Financial Officer (CFO), risk is not an abstract threat but a measurable probability of financial loss. When an executive clearly sees the types of threats, they can develop specific countermeasures for each. In the manufacturing, trading, and service environments of Ukraine today, five main categories of risks can be distinguished, each requiring a distinct approach.

1.1. Operational Risks: Fragility of Processes and Supply Chains

Operational risks are threats related to internal processes, people, systems, or external events that block the company’s ability to function. In wartime conditions, this class of risks has acquired new, menacing forms.

Traditionally, operational risks included equipment breakdowns or product defects. Today, however, we speak of the physical safety of assets and personnel (Staff), energy blackouts (Power cuts), and disruptions in logistics chains. Production stoppages due to lack of electricity or infrastructure damage are a reality that every CFO faces.

But there are less obvious, yet equally destructive aspects. For example, the loss of qualified personnel due to mobilization or migration. In small businesses, knowledge is often undocumented, residing solely in the “heads” of key employees. The loss of a chief technologist or the sole system administrator can paralyze operations more effectively than a missile strike.

Furthermore, operational risks include cybersecurity. With the transition of many processes to the cloud and remote work modes, the vulnerability of SMEs to cyberattacks has grown exponentially. This is not only a risk of data loss but also a risk of operational paralysis due to the blocking of accounting systems.

The key problem with operational risks for SMEs is the lack of redundancy. Large corporations can afford to duplicate servers, warehouses, and production lines. SMEs often operate on a “Just-in-Time” model, which is a sign of efficiency in peacetime but a point of critical vulnerability in wartime. Dependence on a single unique supplier or a single logistics route becomes fatal.

🏛 Practical Case Study: Illustrative Example

In 2022, a light industry manufacturer in Ukraine halted operations due to dependence on a single fabric supplier located in an active combat zone. The company lacked alternative sources because, for years, it had optimized procurement costs while ignoring concentration risk

Solution: A rapid risk analysis allowed the company to find more expensive but reliable alternatives in Romania and Vinnytsia within two weeks. They also implemented a “safety stock” policy, abandoning a pure Just-in-Time (JIT) model.

Classification structures chaos and accelerates decision-making.

1.2. Financial Risks: The Lifeblood of the Business

This is the area of direct responsibility for the CFO, where mistakes become apparent fastest. Financial risks relate to the company’s ability to generate and preserve cash flow.

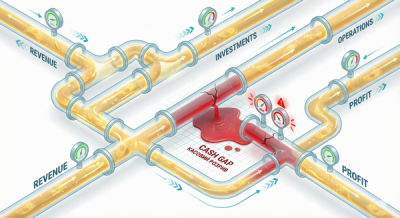

- Liquidity Risk (Cash Gaps): This is the most critical risk for SMEs. Even a profitable company can become insolvent if it runs out of cash to cover short-term obligations. In conditions of unstable payments from clients, this risk becomes a daily threat.

- Currency Risk: For raw material importers or product exporters, exchange rate volatility can erode the entire margin in a matter of days. The lack of hedging instruments for SMEs makes this risk particularly acute. With inflation and currency devaluation, currency risk for importers becomes not just a factor of reduced margins, but a question of solvency.

- Counterparty Credit Risk: Non-payments by partners create a chain reaction. If your key client loses liquidity, you automatically take a hit to your own cash flow.

Practical Aspect: Many SMEs ignore counterparty credit risk, granting deferred payments without checking the client’s financial health. In a crisis, a domino effect of non-payments can destroy even a healthy business in a few months.

1.3. Legal and Regulatory Risks: The Volatility of the Rules

These are risks associated with changes in legislation, tax audits, mobilization procedures, and new requirements for certification or financial monitoring.

Ukrainian business is accustomed to legislative changes, but under martial law, the speed and unpredictability of these changes have increased. The risk lies not only in the changes themselves but in the company’s inability to quickly adapt its processes and accounting systems to new requirements, leading to fines or operational blocks.

For exporters, risks regarding EU regulations (e.g., CBAM or ESG requirements) are added, for which Ukrainian SMEs are often unprepared.

1.4. Reputational Risks: Intangible Capital

In the era of social media and hyper-transparency, reputation is an asset built over years but destroyed in minutes. Negative media coverage, conflicts with staff, or incorrect communication during a crisis can lead to a product boycott or partners refusing to cooperate. Special attention should be paid to associations with “toxic” partners. Under sanctions policies, cooperation with a counterparty having hidden ties to an aggressor country can be fatal for reputation and lead to secondary sanctions.

In the digital age, reputational risk is realized instantly. A single social media post about a company’s incorrect behavior can trigger a boycott. In wartime, society has a heightened sense of justice, so any communication error is multiplied.

Reputation is the asset that is hardest to restore.

1.5. Strategic Risks: The Threat of Relevance

These are risks that the company’s business model will become obsolete or ineffective due to technological changes, the emergence of new competitors, or shifts in consumer behavior. This also includes the loss of key clients or sales markets.

In our reality, the risk of losing markets due to geopolitical factors or the physical impossibility of product delivery is added to this list. For example, the blockade of seaports forced many agricultural enterprises to completely rebuild their logistics and sales strategies, which for many became a matter of survival.

Classification of risks is not merely an exercise in taxonomy. It is the foundation upon which the entire management system is built.

Structuring chaos allows for the transformation of uncertainty into a set of concrete, solvable tasks.

Part 2. Building a Risk Management System: A 5-Step Algorithm

As a CFO, I often hear from SME owners that risk management is expensive and complex. This is a myth. Implementing an effective system does not require a separate department or expensive software. A basic system must be simple, understandable, and, most importantly, actionable. It should be integrated into daily management rituals, not exist as a binder (File) on a shelf.

Step 1. Identification and Description: What Can Happen?

Describe the main risks. Systematically identify sources of risk. Create a risk register. Do not try to cover everything – focus on the top 7 critical threats.

The first step is an honest conversation. Gather your management team (Production Manager, Head of Logistics, Head of Sales, Chief Accountant) and conduct a brainstorming session.

Compile a list of 5–7 key threats that could realistically stop your business. Do not attempt to cover everything at once – focus on the critical. Use SWOT analysis, overlaying it onto a risk map.

It is crucial to involve “frontline” employees in this process. Often, a driver or a shift supervisor sees risks that are invisible from the director’s office. This is the principle of “collective intelligence,” which allows for the detection of blind spots.

Step 2. Assessment and Prioritization: What is the Likelihood and Impact?

Not all risks are equal. Some are catastrophic but unlikely, while others are minor but frequent. To distribute resources effectively, we use a Risk Matrix.

Evaluate each identified risk on two scales from 1 to 5:

- Likelihood (Probability): How likely is it to happen? (1 – almost impossible, 5 – almost guaranteed).

- Impact (Severity): What damage will this cause to finances and reputation? (1 – insignificant, 5 – catastrophe/business stoppage).

By multiplying these two indicators, you get a risk rating. This allows you to divide threats into three zones:

- Red Zone (High Risk): Requires immediate top management intervention. Resources are allocated as a priority. The goal is to reduce either the likelihood or the impact to move the risk into the “yellow” zone.

- Yellow Zone (Medium Risk): Requires constant monitoring.

- Green Zone (Low Risk): We accept the risk as part of doing business.

Step 3. Scenario Planning: What Will We Do?

Write down action scenarios: Algorithms instead of panic.

For every risk in the “Red Zone,” you must have a ready-made action scenario. This should not be a theoretical document. It must be a clear algorithm: “If X happens, we do Y.”

This should be a one-page instruction, understandable to the duty manager at 2:00 AM on a Saturday.

- Example: “If a shipment of raw materials is delayed at customs for more than 3 days -> Notify Production Manager -> Activate procurement from the backup supplier in Ukraine (contacts attached) -> Warn key clients about possible shipment delay.”

Such scenarios turn a stressful situation into a routine procedure of following instructions. This reduces emotional tension and the likelihood of decision-making errors under pressure.

Step 4. Assigning Responsibilities: Risk Owners

Assign responsible persons. Every risk must have an ‘owner’.

Collective responsibility means no responsibility.

A Risk Owner is not necessarily the person to blame for the risk’s occurrence, but the person who has the authority and resources to monitor and minimize it.

- The Head of Procurement or Logistics is responsible for supply disruption risks.

- The CFO is responsible for cash gap risks.

- The Chief Engineer is responsible for technical breakdown risks.

The Risk Owner must regularly report on the status of threats and the state of early warning indicators (which we will discuss later).

Step 5. Monitoring: Does the System Work?

Periodically repeat this cycle, starting from Step 1. Constant supervision of risk status and countermeasure effectiveness. Tracking KRIs (Key Risk Indicators). Regular review of the risk map.

🚛 Practical Case Study: Simplicity That Saves Business

In 2023, a small food distributor in Lviv faced the problem of sudden changes in border crossing rules. Management implemented a simple risk table in Google Sheets, listing key threats: border delays, foreign currency payment refusals, and fuel shortages. For each item, actions and responsible persons were assigned.

Result: When cargo was delayed for 3 days due to border strikes, the team did not waste time on meetings or searching for solutions. The logistics manager immediately activated the backup supply plan from local manufacturers, and the sales department informed clients using a pre-prepared script. As a result, not a single client terminated their contract, and the company avoided penalties for non-delivery.

This case proves: a system works not when it is complex, but when it is understandable and executed.

Risk management is not about complex models. It is about simple actions you can implement this week. The main thing is to start.

Part 3. Key Risk Indicators (KRI): Early Warning System

As a CFO, I see a direct correlation between supply chain reliability and a company’s financial health. A supply disruption is not just a lack of goods in the warehouse. It means frozen working capital, penalties from clients, loss of reputation, and, ultimately, a cash gap. Therefore, in modern conditions, Supply Chain Management becomes part of financial security.

Traditional financial reports (Balance Sheet, P&L) and KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) show us the past. They state facts. For risk management, we need Key Risk Indicators (KRIs). These are “signal flares” that warn of an approaching problem before it hits the balance sheet.

Below is an example of a KRI table, specifically adapted for SMEs, with a distinct focus on the critical “Supply” section.

Key Risk Indicators (KRI) Table

| Department / Function | Key Indicator (KRI) | Description and Formula | Threshold Value (Alarm Signal) | Actions Upon Triggering |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supply Chain | OTIF (On-Time In-Full) | Percentage of orders delivered on time and in full. Reflects supplier reliability. | < 85% or negative trend over 2 months | Supplier audit. Activation of alternative supplier. Increase in safety stock. |

| Supply Chain | Lead Time Variability | Deviation of actual delivery time from planned time. Shows logistics unpredictability. | Deviation > 20% from plan | Review of reorder point. Search for local alternatives to shorten the logistics leg. |

| Supply Chain | Supplier Concentration Index | Share of a single supplier in the total volume of critical raw material purchases. | > 30% of COGS | Launch of a diversification program (Dual Sourcing). Test purchases from new partners. |

| Supply Chain | Partner Financial Health | Presence of lawsuits, tax debts, or negative news about the supplier. | Appearance in debtor registries or negative market signal | Transition to deferred payment terms. Shipment insurance. Reduction of order volume. |

| Finance | Forecast Cash Flow | Difference between expected receipts and mandatory payments (4-week outlook). | < 0 (Deficit) or coverage < 1.2x | Activation of credit line. Negotiations on payment deferrals. Freezing of non-critical expenses. |

| Finance | DSO (Days Sales Outstanding) | Average number of days waiting for payment from clients. Risk of money “freezing.” | Increase > 10% compared to previous period | Halting shipments to debtors. Activation of debt collection. Factoring. |

| Sales | Customer Concentration | Critical dependence. Loss of a client could be fatal. | One client > 20% of revenue (or TOP-3 > 50%) | Accounts receivable insurance. Strategic attraction of new segments. |

| Sales | Churn Rate | Dissatisfaction with product, competitor activity. | > 5% per month (for B2B) or sharp spike | In-depth interviews with lost clients. Review of value proposition. |

| HR (People) | Staff Turnover in Critical Roles | Number of key personnel resignations per period. | > 1 key specialist / quarter | Exit interview. Review of motivation system. Formation of talent reserve. |

| HR (People) | Key Person Risk | Risk of process stoppage due to absence of a key person. | Absence of a deputy for a critical role | Creation of talent reserve, cross-functional training. Process documentation (Knowledge Base). |

Analysis of Supply Metrics

OTIF (On-Time In-Full) is arguably the most important metric on this list. Many companies measure only the fact of delivery, ignoring its quality. But if a supplier delivers goods a week late, or brings only 70% of the order, it creates chaos in your production and sales. A drop in OTIF is often the first signal that your partner is experiencing internal problems they have not yet disclosed. Monitoring this metric allows you to act proactively, changing cooperation terms before the supplier fails you at a critical moment.

Lead Time Variability is an indicator of logistics stability. If the standard delivery time is 10 days, but in reality, it fluctuates between 8 and 20 days, you cannot plan production based on the Just-in-Time principle. You are forced to hold excess inventory (Stock) to cover this uncertainty. Increased variability is a signal for the need to increase buffers or change the logistics route.

Integrating these KRIs into weekly reporting allows a manager to keep a finger on the pulse of the business and see threats on the horizon, rather than when they have already stormed the office.

Important: KRIs are effective only when a specific action is assigned to each indicator. If an indicator “flashes red,” the system must react automatically, without waiting for a board meeting.

Part 4. The Philosophy of Antifragility: Lessons from Nassim Taleb

In the classical school of financial management, we were taught to strive for maximum efficiency. The mantras were “inventory minimization,” “Just-in-Time,” and “cash balance optimization.” It was believed that money sitting in an account was “dead” capital that wasn’t working. In a stable world, this increased Return on Investment (ROI). However, in a world of extreme uncertainty, such “efficiency” becomes a synonym for vulnerability.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, a financial trader, mathematician, and philosopher, in his seminal work The Black Swan, upended the understanding of risk. He introduced the concept of rare, unpredictable events that have a colossal, often catastrophic impact. Full-scale war, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the global financial crisis of 2008 are classic “Black Swans.” Taleb argues: we are fundamentally incapable of predicting such events, so any models based on forecasting the future from the past are flawed.

From Robustness to Antifragility

Taleb distinguishes three states of systems:

- Fragile: A system that breaks under stress or uncertainty. Example: a business with high debt, zero inventory, and one client. Any shock is fatal for it.

- Robust: A system that withstands stress without changing. Example: a business with financial reserves that can survive a crisis but does not change.

- Antifragile: A system that gets better as a result of stress.

For Ukrainian SMEs, the goal should not be mere robustness, but antifragility. What does this look like in practice? It is a business that uses the crisis as an opportunity for expansion. When competitors built on the principle of “maximum efficiency” (with no inventory or reserves) halt due to broken supply chains, an antifragile company that held strategic reserves and diversified suppliers captures their market share. It gains from chaos.

The Necessity of Reserves for Unpredictable Risks

A key element of antifragility is Redundancy. In nature, we have two kidneys and two lungs, although one is sufficient for survival. Nature does not optimize the organism for “efficiency”; it optimizes it for survival. In business, the role of the “second kidney” is played by reserves (buffers).

Creating reserves often provokes resistance from owners, as these are “frozen” funds. However, as a CFO, I insist: these are not lost opportunities; this is the cost of a survival option.

1. Financial Buffer (Cash Buffer)

This is your “freedom fund.” A rule of thumb for a financially stable SME: you must have liquidity covering 3–6 months of fixed operating expenses (rent, critical personnel, taxes, security) assuming a complete halt in receipts. This reserve buys you time – the most valuable resource in a crisis. Time to make balanced decisions, find new markets, and repurpose production, without being in a state of panic due to the inability to pay wages tomorrow.

2. Inventory Buffer

Moving away from pure “Just-in-Time” in favor of “Just-in-Case” for critical items. The calculation of safety stock should be based not on average metrics, but on peak risks.

Formula: Buffer = (Max Daily Consumption × Max Lead Time) – (Average Consumption × Average Lead Time).

If your supplier brings goods across an unstable border, increasing warehouse stock is not an “inefficient use of working capital”; it is a guarantee that you will not stop production and will not let customers down while competitors wait for blocked cargo.

3. Time Buffer

In any project planning (whether construction, IT product development, or launching a new line), it is necessary to build in a time buffer (20–30%) to the critical path. This is protection against the “planning fallacy” – a cognitive bias where people systematically underestimate the time needed to complete tasks. This buffer allows for absorbing inevitable delays without missing final deadlines and without stress for the team.

Philosophy Summary: We acknowledge that the world is complex and unpredictable. Therefore, we consciously sacrifice part of short-term efficiency and profitability (by holding reserves) for the sake of long-term resilience. This is our fee for the right to stay in the game when a “Black Swan” arrives.

Part 5. The Human Factor: The Role of Leader and Team in Risk Management

The most perfect risk management system described in regulations is not worth the paper it is printed on if it does not live in the company’s culture. Effective risk management depends not on spreadsheets, but on people. It is a team game where every employee is a sensor gathering information about the surrounding environment.

The Role of the Leader

The task of top management is not just to control, but to create an environment. It is the leader who:

1. Defines priorities: Which risks are critical for the business?

The leader must clearly articulate which risks are acceptable and which are not. For example: “We are willing to take risks when launching new products, but we have zero tolerance for risks related to product quality or personnel safety.” This gives the team clear boundaries for independent decision-making.

2. Shapes culture: Do employees speak openly about problems?

This is critically important. In many organizations, there is a culture of “shooting the messenger” who brings bad news. As a result, problems are hushed up at lower levels until they grow into a catastrophe. The leader must encourage early reporting of problems. The phrase “Boss, we have a potential issue with a supplier” should be perceived as a sign of professionalism, not failure.

3. Delegates authority: Who is responsible for analysis and response?

The CEO cannot know everything. A shift supervisor (Foreman) knows the condition of the equipment better than the plant director. The Risk Owner must be as close as possible to the source of the risk.

The Role of the Team

Top management creates the system: the rules and the environment. But it is the team that:

1. Reports threats from the front lines.

“Frontline” employees (drivers, sales managers, machine operators) are the eyes and ears of the company. They are the first to notice “weak signals” that precede a crisis.

- A sales manager might hear rumors from a client about a competitor’s or partner’s financial trouble.

- A logistician sees growing queues at the border long before official announcements.

- A driver knows about road deterioration on a critical route.

2. Proposes solutions.

3. Implements crisis plans.

When risk management becomes part of the company culture, decisions are made faster, information is not lost, and mistakes are not repeated. This works in both small businesses and large structures.

Practical Tip: Implement a rapid feedback mechanism. This could be a simple “Operational Risks” chat in a messenger or a five-minute stand-up (Daily Huddle) at the morning meeting, where anyone can voice a potential threat without unnecessary bureaucracy and propose a solution.

🌾 Practical Case Study: The Power of Communication

An agricultural enterprise in southern Ukraine in 2023 faced the threat of crop loss due to abnormal drought and irrigation problems. The manager introduced a “Weekly Risk Dialogue” initiative. Every department head (agronomist, engineer, mechanic) had to present 1–2 risks they saw in their area of responsibility at the meeting, along with response ideas.

Result: Thanks to this approach, the chief mechanic reported the risk of irrigation pump wear and tear in advance, and the procurement department managed to find scarce spare parts before the critical season began. The company avoided an emergency shutdown of the irrigation system, which could have cost them the entire year’s harvest.

This example illustrates that risk management is not about paperwork, but about communication and engagement.

Risk management is a team sport. Open communication, employee engagement, and leader support form the company’s resilience to challenges.

Part 6. Integration into Strategy: From SWOT to KRI

Strategic planning without considering risks is like building a castle on sand. Risk management should not be a separate process; it must be “embedded” into the DNA of your development strategy. When you plan a market entry or a new product launch, the question “what can go wrong?” should be just as important as “how much will we earn?”.

Tools of Integration

1. SWOT + Risk Analysis:

Classic SWOT analysis is often done as a formal check-the-box exercise. Make it actionable: overlay your risk map onto your strengths and weaknesses. How do your weaknesses (e.g., outdated IT) correlate with external threats (cyberattacks)? This will reveal the most vulnerable spots.

2. Scenario Planning:

Instead of one linear budget (“we will grow by 10%”), develop 2–3 development scenarios:

- Optimistic (Upside): The war ends, markets open.

- Realistic (Base Case): The current state drags on (Status Quo).

- Pessimistic (Downside / Stress Test): Blackout, border closures, demand drop by 30%.

For each scenario, calculate the financial result and resource requirements. This allows you to be ready to change course without panic.

3. Key Risk Indicators (KRI):

Set the digital markers we discussed in Part 3. They must be integrated into the management dashboard alongside sales and profit metrics.

🌍 Practical Case Study: Strategic Foresight

In 2023, a Ukrainian manufacturer of frozen foods planned an expansion into the Balkan market. It was an attractive opportunity, but the team conducted a deep risk analysis before starting. Key threats were identified: customs delays for perishable products, EU certification issues, and currency risks.

Instead of abandoning the project or risking “blindly,” the company developed a risk minimization strategy:

- Implemented export contract insurance.

- Created a buffer warehouse в Угорщині (Near-shoring), which negated the risk of border delays.

- Developed a dual logistics route.

Result: When carrier strikes began at the Polish border, the company was able to fulfill its obligations to Balkan partners without disruption using the reserve warehouse. This allowed them not only to keep contracts but to strengthen their reputation as a reliable partner while competitors stood in queues.

A strategy that considers risks is not a limitation, but a safeguard against catastrophes. It allows acting confidently without losing flexibility.

Part 7. How to Verify That Your Risk Management System Works

A risk management system is not a “fire-and-forget” initiative. It is a dynamic process. Risks mutate, market conditions change, and new threats emerge. Even if you have a binder full of instructions, the key question is: will it work in reality when the “server goes down” or “customs stops”?

In real business, it is important not just to have documents, but to regularly evaluate the effectiveness of actions, reaction speed, and system adaptability. As a CFO, I recommend conducting regular controls of your security system.

Signs of a Living and Effective System:

- Awareness: You and your top managers can name the company’s top 3–5 risks at the current moment without prompting.

- Readiness: Critical events do not catch the company off guard – action scenarios exist, and, crucially, the necessary resources (reserves) are available.

- Clarity of Action: Responsible persons (Risk Owners) clearly know their algorithm of actions in the event of a crisis. They do not need to call the CEO to ask what to do during a power outage – they act according to protocol.

- Learning: A post-incident review is conducted after any event. A mistake made once is experience. A mistake repeated twice is a lack of a system.

How to Conduct an Assessment (Risk Audit):

- Incident Audit: Analyze the problems that occurred over the last year. Were they foreseen in the risk map? If not, why? This will reveal blind spots.

- Stress Testing: Conduct a crisis simulation. For example, on paper, “turn off” your revenue inflow for a month. Are reserves sufficient? What will you cut first?

- Employee Survey: Ask rank-and-file employees if they know how to report a potential problem. If they are afraid or do not know how, your notification system is broken.

- Risk Map Update: How long ago did you review your matrix? In our conditions, this must be done at least quarterly.

🚛 Illustrative Example: Audit as an Improvement Tool

Situation: In 2023, a Kyiv logistics company faced a series of cargo delays, leading to customer dissatisfaction. Management decided not just to punish the guilty parties but to conduct an internal audit of the risk management system.

🔍 Audit Diagnosis: It turned out that response policies existed, but some new employees were not even aware of them. Communication between the sales department and logisticians was broken.

Solution: The result of the audit was an internal training program, the implementation of regular short “risk meetings,” and automated client notifications about cargo status.

📊 Result: Over the next 6 months, the number of incidents requiring manual top management intervention decreased by 70%. The company began to work like a clockwork mechanism, rather than a collection of firefighting teams.

Conclusion: Your “Insurance Policy” in a World of Chaos

Systemic risk management for Ukrainian SMEs is not a restriction on entrepreneurial freedom, nor is it a bureaucratic exercise. It is your “insurance policy” that you write for yourself. In a world where crises are becoming the new normal, the winner is not the one who ignores threats hoping for luck, but the one who knows how to manage them.

Creating an antifragile system requires discipline. It requires freezing part of the capital in reserves. It requires honest conversations about unpleasant things. But in return, it gives you something priceless – confidence. Confidence that you can protect your business, your people, and your assets, no matter what tomorrow brings.

Start small today. Do not try to build a perfect system in one day.

- Describe your top 5 risks.

- Check your financial buffer.

- Look at your suppliers through the prism of KRIs.

This is the job of the CFO and the company leader – transforming uncertainty into managed risk, securing the company’s future.