Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

Introduction: Beyond the Balance Sheet — Why I Consider Culture Our Most Undervalued Asset

Throughout my career as a Chief Financial Officer, I have repeatedly seen companies fail by ignoring one critical, albeit intangible, asset — their culture. We have grown accustomed to relying on technology, market share, and operational efficiency as solid pillars, but in today’s unstable environment, they are becoming increasingly ephemeral. Continuing to bet solely on them is ignoring reality.

And the reality is that companies with a strong culture demonstrate four times higher revenue growth. For me, as a CFO, this transforms the conversation about culture from an abstract discussion into a hard financial calculation.

For the modern CFO, whose role has evolved from a guardian of financial data to a key strategic partner, ignoring culture is not just a missed opportunity but a strategic miscalculation. Culture is the invisible architecture that supports every aspect of our performance, from employee engagement to financial results. It impacts everything: from operating costs and risk management to innovation and long-term growth.

As a steward of enterprise value, I can no longer afford to view culture as an abstract concept belonging solely to HR. I perceive it as a critical, manageable asset that has a direct impact on the P&L, Balance Sheet, and company valuation.

But how do we analyze, measure, and purposefully shape such a complex phenomenon? For myself, I found the answer in a powerful diagnostic tool — the “Cultural Web” model. This model serves as a compass, allowing us to decompose the organization’s DNA into components, understand their interconnection, and, most importantly, develop a practical roadmap for aligning culture with strategic and financial goals.

In this article, I want to share my perspective on the “Cultural Web,” demonstrate its direct link to key financial metrics, and offer a practical methodology for its application, positioning culture as a central element in the modern financial leader’s arsenal.

1. Decoding Organizational DNA: An Introduction to the “Cultural Web”

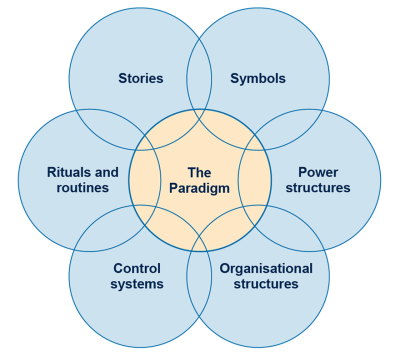

To effectively manage culture, one must first understand it. The “Cultural Web” model, developed in 1992 by Gerry Johnson and Kevan Scholes, provides a structured approach for diagnosing and analyzing the complex, often hidden aspects that shape organizational life.

1.1. The Central Paradigm

At the heart of the “web” lies the Paradigm. This is not merely the company’s mission or vision; it is a set of deep-seated, often unspoken beliefs, assumptions, and values that define “the way things are done around here.”

The Paradigm is the collective experience of the organization and its lived reality from an employee’s perspective. It is a synthesis of six surrounding elements and dictates the organization’s worldview, its approach to problem-solving, and strategic decision-making. The Paradigm is what employees take for granted, what is rarely questioned, and what guides their behavior when explicit instructions are absent.

1.2. Six Interconnected Elements

Парадигма формується та, своєю чергою, підкріплюється шістьма елементами, які представляють відчутні, поведінкові та символічні прояви культури. Ці елементи включають: історії, ритуали та звичаї, символи, організаційні структури, системи контролю та структури влади.

It is crucial to understand that the “Cultural Web” is not just a static snapshot, but a dynamic systemic map.

The six elements are not independent variables; they form a feedback loop that reinforces one another. A change in one element (e.g., modifying Control Systems to reward collaboration) creates tension and pressure on others (e.g., challenging old Stories about individual heroes). This is exactly how strategic cultural change is initiated.

Many transformation initiatives fail precisely because they ignore this interconnection. From my experience, you cannot simply change a financial incentive (Control System) and expect the culture to shift. You must also consider how to create new Stories of success, new Rituals of teamwork, and new Symbols of recognition to support this change. The model provides a holistic checklist to ensure a systemic, rather than fragmented, approach to change.

2. Six Forces Shaping Your Financial Result

Each of the six elements of the “Cultural Web” is a powerful force that directly or indirectly influences operational efficiency and the financial health of the organization. Understanding these forces is the first step toward consciously leveraging them to achieve strategic goals.

2.1. Stories and Myths: Narratives Defining Value

- Definition: These are anecdotes, legends, and narratives circulated within the organization about its history, successes, failures, heroes, and villains. They constitute the “collective memory” and convey information about what behavior and values are truly prized.

- Business Impact: Stories are powerful learning tools that induct new employees into the culture and reinforce norms. Tales of overcoming adversity build resilience, while stories about innovator founders can cement a culture of innovation (e.g., the story of the Ukrainian monobank, created by former PrivatBank executives to completely disrupt the outdated banking experience). Conversely, negative stories can perpetuate a toxic culture (e.g., the narrative at the British bank Barclays of “every man for himself”).

- My Perspective as CFO: What stories are told here about cost-saving initiatives? Are they tales of smart innovation or painful, arbitrary cuts? The narratives surrounding financial decisions shape employee perception and their future behavior.

2.2. Rituals and Routines: Behavior Driving Efficiency

- Definition: These are daily, repetitive actions and behaviors that signal what is acceptable and normal. This includes everything from how meetings are conducted and decisions are made, to how customers are served and successes are celebrated. Rituals are routines imbued with symbolic meaning and intent.

- Business Impact: Routines can either reinforce efficiency and quality or entrench unproductive habits. Rituals, such as a weekly team lunch or an annual awards ceremony, create social cohesion, psychological safety, and a sense of belonging, which is linked to higher productivity. The Agile culture of the Swedish company Spotify, with its autonomous “squads,” “tribes,” and regular hack weeks, is a powerful ritual that reinforces its culture of innovation and flexibility.

- My Perspective as CFO: Processes like budgeting, performance reporting, variance analysis, etc., are powerful corporate rituals. Are they collaborative, future-oriented exercises that empower managers, or are they antagonistic, retrospective interrogations that encourage sandbagging and fear? The nature of these financial rituals directly shapes our organization’s agility and strategic alignment.

2.3. Symbols: The Visual Language of Your Strategy

- Definition: These are the visual representations of the organization, including logos, office design, dress code, status symbols (e.g., reserved parking spaces or executive dining rooms), and even the language or jargon used.

- Вплив на бізнес: Символи потужно та швидко передають інформацію про статус, цінності та владу. Офіс відкритого планування символізує співпрацю, але водночас створює труднощі для зосередженої роботи. Закриті офіси можуть забезпечити концентрацію, але ризикують посилити ієрархію та спричинити інформаційні ізоляції. Тому все більше компаній обирають гібридні моделі: зони співпраці, тихі кімнати для фокусування та гнучке «гаряче» використання робочих місць.

The famous monobank cat mascot, symbolizing a departure from banking bureaucracy in favor of simplicity and humanity, or easyJet‘s recognizable orange color, conveying energy and the accessibility of their low-cost model, are powerful symbols that instantly communicate key brand values. These visual cues shape the perceptions of both employees and customers.

- My Perspective as CFO: Capital expenditure (Capex) on office space is a financial decision with deep cultural symbolism. Investing in state-of-the-art collaborative spaces sends a different signal than investing in a luxurious, isolated executive floor. This choice signals what we truly value: hierarchy or collaboration.

2.4. Organizational Structures: Charts of Power and Agility

- Definition: This includes both the formal, written organizational chart (hierarchical vs. flat) and, crucially, the unwritten, informal lines of influence and communication. It defines roles, reporting lines, and how work flows through the organization.

- Business Impact: A rigid, hierarchical structure (“tall-narrow”) can be effective in a stable environment but stifles innovation and slows reaction time, often fostering a “role culture” where protecting one’s turf is more important than getting the job done. A “broad-flat” structure, like at the Spanish company Inditex (Zara), can foster a “task culture” focused on agility and customer service. Siloed structures are a major barrier to efficiency and cross-functional innovation.

- My Perspective as CFO: Organizational restructuring is often driven by cost-cutting, but I always analyze its cultural impact. Delayering (simplifying the hierarchy) may reduce the payroll fund but will fail if the underlying power structures and control systems do not also change to empower employees. Structure dictates how financial information flows, influencing the speed and quality of decision-making.

2.5. Control Systems: Measuring What Truly Matters

- Definition: Formal and informal processes used to monitor, measure, and direct employee actions. This includes financial systems, quality control systems, performance appraisals, and especially reward and recognition systems (bonuses, promotions).

- Business Impact: Organizations get the behavior they measure and reward. If control systems reward exclusively individual sales volume, they will demotivate teamwork and customer satisfaction. The Irish airline Ryanair’s intense focus on metrics like aircraft turnaround time on the ground and maximum staff utilization creates a culture of extreme cost efficiency.

- My Perspective as CFO: This is my traditional area of responsibility, but I view it through a cultural lens. The design of financial control and incentive systems is one of the most powerful levers for shaping culture. By designing a bonus system that rewards cross-functional team success in addition to individual performance, I am actively building a culture of collaboration.

2.6. Power Structures: The Real Centers of Influence

- Definition: Individuals or groups that hold real power and wield the most influence over decisions, operations, and strategic direction. This may or may not align with the formal organizational chart. Power can be concentrated in the hands of one leader (“power culture”) or distributed among experts or teams (“role culture”).

- Business Impact: The beliefs and priorities of the dominant power structure become the de facto values of the organization. If a key group of senior engineers holds informal power and resists a new strategic direction, their influence can sabotage the initiative, regardless of the CEO’s statements. Identifying and engaging these true centers of power is critical for any change effort.

- My Perspective as CFO: I must understand who truly influences major investment decisions and resource allocation. Is it the formal executive committee, or a small group of influential unit heads who can informally veto projects? Understanding this political landscape is essential for effective capital allocation and strategy execution.

It is crucial to understand that the power structure is not just about titles; it is about the leader’s belief in their people. Are you building processes based on total control (Theory X) or on trust (Theory Y)? Read more about how these deep-seated managerial beliefs become a self-fulfilling prophecy for the entire team in my separate article: Management Style: How Your Expectations Program Your Team’s DNA.

2.7. The Ukrainian Context: Examples I Observe

To see how these elements work not just in theory but in practice, I look at the experience of leading Ukrainian companies that consciously build their culture.

- Stories and Myths: I observe with interest how Rozetka, realizing the risk of cultural fragmentation, created the “Rozetka Book of Things We Believe In.” This is an excellent attempt to codify key stories and values, uniting thousands of employees around a shared narrative of customer-centricity.

- Rituals and Routines: The IT company MacPaw has a ritual of weekly “family lunches.” This seemingly simple routine strengthens informal bonds and reinforces the value of “Stay Human,” creating an atmosphere of trust that, I am certain, positively impacts productivity.

- Symbols: The transformation of the Metinvest service unit into the IT company Metinvest Digital was accompanied by a change in symbols. The stereotypical image of the “tech guy in a hoodie” gave way to a more business-like style, symbolizing the transition from internal support to the position of a responsible business partner. A transformation of employee positioning began: from “I perform standard service tasks” to “I provide a quality service to the client.”

- Control Systems: Nova Poshta embedded the principle “Discipline and fulfilling obligations are part of our culture: strictly on time, no exceptions” into its Corporate Ethics Code. For me, as a CFO, this is a vivid example of how a control system element is directly linked to service quality and operational efficiency.

- Power Structures: The IT company Genesis declares that they “value people who achieve results and give them maximum freedom and resources.” This indicates a meritocratic power structure where influence is granted based on performance, stimulating innovation and personal responsibility.

- Paradigm: The creative agency Banda articulates its paradigm through the mission “to make creativity significant.” This fundamental belief defines their approach to everything, transforming “work relationships into friendships.”

Table 1. “Cultural Web” Diagnostic Toolkit

To turn theory into practice, management needs a self-analysis tool. This table consolidates diagnostic questions scattered across various studies into a unified, structured system for analyzing one’s own organization.

Table 1. “Cultural Web” Diagnostic Toolkit

| Element | Description | Key Diagnostic Questions for Senior Management |

| Stories and Myths | Narratives that convey values, beliefs, and behavioral norms. | • What stories are told about our company? • Which heroes, villains, and rebels feature in them? • What do these stories say about what we believe in and value? • What narratives are passed on to new employees? |

| Rituals and Routines | Daily behaviors and actions that signal acceptable norms and expectations. | • What behavior do these routines encourage? • What would be immediately noticeable if changed? • What core beliefs do these rituals reflect? • How do we make decisions and conduct meetings? |

| Symbols | Visual representations of the organization, including logos, office space, dress code, and language. | • What image is associated with our organization from the perspective of clients and staff? • Are status symbols used? • Do our symbols resonate with our stated values? |

| Organizational Structures | Formal and informal hierarchies defining lines of power and communication. | • Is our structure flat or hierarchical? Formal or informal? • Where do the formal and informal lines of authority lie? • Does the structure encourage fairness and collaboration? |

| Control Systems | Processes for monitoring, measurement, and rewarding performance. | • What behavior do our reward systems actually incentivize? • Do we reward heroes who put out fires, or architects who prevent them? • Who gets promoted, and why? • Which processes have the tightest control, and which have the weakest? |

| Power Structures | The real centers of influence, which may not align with the official structure. | • Who holds real power in the organization? • What do these people believe in and champion? • Who makes or influences key decisions? • How is this power used or abused? |

3. Culture ROI: Quantifying the Link Between the “Web” and Financial Health

For me, as a Chief Financial Officer, the most critical task is to translate conceptual models into measurable financial outcomes. This section presents compelling evidence of how the “soft” elements of the “Cultural Web” directly impact the “hard” numbers in our financial statements.

3.1. Driving Revenue Growth and Profitability

- The Mechanism: A positive culture, characterized by high employee engagement, trust, and psychological safety, is not a consequence of success but its leading indicator. Engaged employees provide better customer service, are more productive, and more innovative.

- Key Data I Rely On:

- Companies with a strong culture demonstrate 4x higher revenue growth.

- Businesses with high engagement have 23% higher profitability than their less engaged competitors.

- Companies on the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For list outperform the market by 3.68 times in stock returns.1

- Cultural factors can explain 40–50% of the performance difference between high- and low-performing companies in the same industry.2

- Connection to the “Web”: A culture with positive “Stories” of employee empowerment, inclusive “Rituals,” and fair “Control Systems” directly contributes to engagement, which is the driver of these financial results.

3.2. Mastering Efficiency and Operational Excellence

- The Mechanism: A culture focused on operational excellence is a two-way process. On one hand, it is disciplined cost management; on the other, it is a relentless pursuit of efficiency improvement. This approach transforms optimization from a “top-down” directive into a shared responsibility of the entire organization.

- Case Studies:

- Cost Control Culture (Ryanair): The culture of the Irish airline is a textbook example of ruthless cost control. From using a single aircraft type to reduce maintenance costs to minimizing turnaround time on the ground—every aspect of their operations (“Routines” and “Symbols”) is subordinated to the paradigm of lowest cost. This allows them to remain a leader in their segment, but such an approach requires rigid discipline.

- Continuous Improvement Culture (Porsche): The German car manufacturer is a vivid example of Kaizen philosophy in European business. Their production system is built on the principle of constantly seeking and eliminating waste (muda) at all levels. Every employee, from engineer to assembly line worker, is involved in the improvement process. This is not just about cutting costs, but about enhancing quality, reducing lead times, and optimizing every movement. Such a culture transforms efficiency from a one-time project into a daily “Ritual” and a source of pride (“Stories”).

Tools for Building a Culture of Efficiency

For me, as a CFO, it is important to rely on proven methodologies. In addition to the 5C model, which perfectly structures the cost management approach, I consider it necessary to integrate two powerful philosophies into the corporate culture:

- Kaizen Philosophy: This approach, meaning “continuous improvement,” engages every employee in the optimization process. It teaches the team not to tolerate inefficiencies but to constantly seek opportunities for small but regular improvements. From a financial perspective, the cumulative effect of thousands of small improvements often exceeds the result of a single large but risky project.

- Theory of Constraints (TOC): Developed by Eliyahu Goldratt, this theory teaches us to focus on the system’s weakest link—the “bottleneck” or constraint. Instead of trying to improve everything at once, TOC suggests directing all efforts toward expanding the capacity of this specific constraint. This requires a cultural shift: not all units should work at 100% capacity. Those upstream of the “bottleneck” must work at its pace to avoid creating excess inventory (which freezes working capital). This is a counterintuitive but extremely effective approach to increasing overall system productivity.

While the successful implementation of these philosophies requires the effort of the entire team, their correct embedding into Control Systems depends on the CFO. As a financial leader, I can directly facilitate this:

- For Kaizen: Allocate a special, easily accessible “micro-improvement fund” in budgets so that teams can quickly finance and test their initiatives without going through a full bureaucratic approval cycle.

- For TOC: Transform internal financial (managerial) reporting by shifting the focus from measuring the local efficiency of each unit to the end-to-end throughput of the entire system, emphasizing the productivity of the “bottleneck.”

3.3. Optimizing Risk Management and Capital Allocation

- The Mechanism: Organizational culture is the foundation of its risk management system. Prevailing attitudes toward risk-taking, transparency, and accountability determine the effectiveness of any formal Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) process.

- Data and Insights:

- When management prioritizes aggressive growth and is willing to take significant risks, it often leads to less mature ERM processes.

- Internal demands from the CEO/Board for better risk oversight significantly improve ERM maturity, but this effect is weakened by the perception of resource constraints. This highlights a critical tension that I, as a CFO, must manage.

- Hierarchical cultures (“Power Structures”) tend to be risk-averse and slow to react, while innovative, entrepreneurial cultures support calculated risk-taking aligned with strategy.

My Role in Investment Decisions: Culture directly influences investment decisions. A culture with low tolerance for uncertainty will favor safe, evolutionary projects, potentially missing opportunities for transformational growth. A culture that perceives failure as an integral part of learning (reflected in its “Stories” and “Rituals”) encourages experimentation necessary for innovation and long-term value creation.

Corporate culture is a non-diversifiable internal risk factor that directly affects the company’s cost of capital and valuation multiples. Investors and analysts increasingly view culture as an indicator of operational risk and future performance. Therefore, I consider culture management a core component of my fiduciary duty. A negative culture directly transforms into a tangible financial penalty through a lower market valuation of the company. I view cultural initiatives not as expenses, but as investments in reducing business risks and increasing market value.

Table 2. Mapping Culture to Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

This table creates a clear, undeniable link between the elements of the “Cultural Web” and the metrics that matter most to me and my team. It serves as a bridge between the world of culture and the world of finance.

| Cultural Web Element | Desired Cultural Trait | Impact on Financial KPIs | Impact on Strategic KPIs |

| Control Systems | Reward systems incentivize long-term value creation and collaboration. | ROIC (Return on Invested Capital), Staff Turnover Cost, R&D Productivity. | CSAT (Customer Satisfaction Score), EES (Employee Engagement Score). |

| Stories and Myths | Narratives celebrate innovation and learning from mistakes. | Revenue Growth from new products, CLV (Customer Lifetime Value). | Time-to-Market for new products, Innovation Index. |

| Rituals and Routines | Budgeting processes are collaborative and forward-looking. | Forecast Accuracy, Opex Efficiency. | Strategic Agility, Decision-making Speed. |

| Organizational Structures | Flat, agile structure facilitates cross-functional communication. | SG&A (Selling, General & Admin expenses) as % of revenue. | Cross-team collaboration efficiency, Market response speed. |

4. From Diagnosis to Action: My Approach to Cultural Transformation

Analysis is just the first step. True value lies in converting insights into concrete actions that lead to measurable results. Here, I offer a practical, step-by-step guide for applying the model, illustrated by a compelling real-world business example.

4.1. The Four-Step Transformation Process

- Step 1: Analyzing the Current Culture (“As-Is”)

I use the “Cultural Web” and the diagnostic questions from Table 1 to create a map of the current reality. It is crucial to gather data via interviews, surveys, and observations. And to be brutally honest about the gaps between the stated culture and real practice.

- Step 2: Defining the Desired Culture (“To-Be”)

Next, we create a new “Cultural Web” that is clearly aligned with the organization’s long-term strategy. Which “Stories,” “Rituals,” and “Control Systems” do we need to achieve our strategic goals?

- Step 3: Identifying Gaps and Developing a Change Plan

Comparing the two “webs” allows us to identify the most critical gaps. This comparison shows exactly which elements need changing. Based on this, we develop a detailed plan that systemically covers each of the six elements.

- Step 4: Implementation, Monitoring, and Reinforcement

We execute the plan, utilizing my oversight of resource allocation and performance management to drive the transformation. We constantly track progress using the KPIs defined in Table 2 and adjust the plan as needed.

4.2. Transformation Example: Siemens’ “Vision 2020” Program

- The “As-Is” Situation: In the early 2010s, the German conglomerate Siemens faced the need to adapt to new market realities where digitalization and agility were becoming key. The existing structure and culture were too bureaucratic and slow for effective competition.

- The “To-Be” Vision: In 2014, the “Vision 2020” program was launched. Its goal was to transform Siemens into a faster, more agile, and focused company by creating an “ownership culture” and concentrating on the growth markets of electrification, automation, and digitalization.

Applying the “Web” (Implicitly):

- Control Systems: New clear financial targets were set, such as productivity gains of €1 billion by the end of 2016 and annual cost productivity growth of 3–5%. Simultaneously, to stimulate an “ownership culture,” the company committed to increasing the number of employee shareholders by 50%.3

- Organizational and Power Structures: An entire layer of management — “Sectors” — was eliminated, and divisions were bundled. This decision aimed to reduce bureaucracy, cut costs, and accelerate decision-making by transferring more authority directly to business units.

- Symbols: The name of the program itself, “Vision 2020,” became a powerful symbol of change. Additionally, strategic acquisitions (e.g., part of Rolls-Royce’s energy business) and portfolio reorganization symbolized a decisive departure from old priorities and a focus on new technological directions.

Financial Results: This cultural and strategic transformation yielded concrete financial results. The company achieved the planned cost reduction of €1 billion. The profit margin of underperforming businesses, which was at -4% in 2013, rose to +3% in 2016, demonstrating the effectiveness of the new management approach and culture of accountability. For me, this case is undeniable proof of the financial ROI of a well-executed cultural transformation.4

Conclusion: My Role as CFO — Culture Architect

The role of the CFO has expanded significantly beyond traditional financial management. Today, the CFO is a central figure in strategy execution, digital transformation, and data analytics. As the budget owner and final arbiter of performance metrics, I hold the most powerful levers for shaping organizational behavior.

A deep understanding of the organization’s “Cultural Web” is no longer a “nice-to-have” for me, but a core competency for strategic financial leadership. I must transition from the role of a bean counter to the role of a “Culture Architect,” proactively designing and nurturing a culture that creates a sustainable competitive advantage.

Ultimately, an organization’s culture is its ultimate performance management system. It dictates what is valued, how decisions are made, and how people behave when no one is watching. The CFO who masters the ability to read and shape this system is the one who will deliver superior, sustainable value in the decades to come.

Sources:

- According to FTSE Russell research, companies on the Fortune 100 Best Companies to Work For® list outperform the market by a factor of 3.68. Great Place To Work, accessed 2025-10-20, https://www.greatplacetowork.com/press-releases/100-best-companies-to-work-for-deliver-staggering-business-performance ↩

- Relationship Between Corporate Culture And Growth, LSA Global, accessed 2025-10-20. https://lsaglobal.com/blog/relationship-between-corporate-culture-and-growth/ ↩

- Siemens – Vision 2020, Siemens Press Release, accessed 2025-10-20. https://press.siemens.com/global/en/pressrelease/siemens-vision-2020 ↩

- Siemens Vision 2020 – Focus on profitable growth, Siemens Investor Relations Presentation, accessed 2025-10-20. https://www.siemens.com/investor/pool/en/investor_relations/financial_publications/speeches_and_presentations/170322_presentation_bofaml_conference.pdf ↩