Why Accounting Cost Is a Poor Criterion for Decision-Making

Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

We have already examined cases where selling products below cost can actually increase enterprise profit (see Costing Traps (Part 1)).

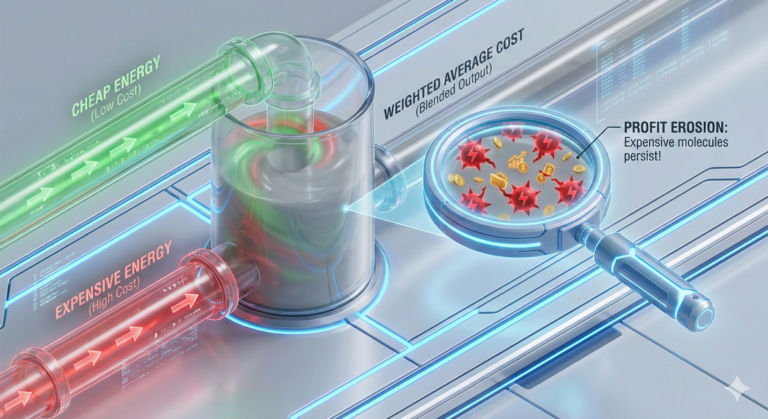

However, even when using Variable Costing (Marginal Costing) for decision-making, erroneous decisions can still be made. Let’s consider a situation where a product is manufactured using a resource from different sources (batches) with significantly different costs. Relying on variable cost calculated via the Weighted Average Cost (WAC / AVCO) method can lead to flawed decisions regarding the production and sale of additional product batches, ultimately reducing the enterprise’s profit.

A Real-World Business Case

Let’s look at a case from a real business. An enterprise manufactures two types of products. Production of one type generates heat, while the other consumes heat. Heat from the production of Product 1 is insufficient, so producing Product 2 requires purchasing natural gas to generate the additional volume of heat needed.

The enterprise used the Weighted Average Cost method for inventory valuation.

Product 2 is sold to various European regions on a delivered basis. Delivery locations range from a few dozen kilometers away from the plant to the other side of Europe. Consequently, the net selling price (sales price minus delivery cost) fluctuates within a wide range.

The Flawed Algorithm

The following algorithm was used to make decisions about the production and sale of Product 2:

- Selection: For preliminary sales planning, orders for Product 2 were selected at prices higher than the variable cost of the previous month.

- Planning: Raw material purchases and Product 2 production were planned based on the projected sales volume (taking inventory balances into account).

- Costing: The cost of planned Product 2 production was calculated based on planned raw material purchase prices and other direct costs.

- Adjustment: The obtained planned variable cost was compared with the minimum planned sales prices. Sales volumes were adjusted if necessary.

- Result: The full cost of planned sales was calculated, and planned profit was determined.

Crucially: The cost of heat used for Product 2 was calculated using the Weighted Average Cost method.

The Flaw of Averages

The Commercial Director assumes that every sale priced above the variable cost increases profit. For calculations, there is only one cost for this product type, correctly calculated using an acceptable method (WAC).

At first glance, the logic of such planning appears flawless – the minimum selling price is higher than the variable product cost (Fig. 1). In this graph, the cost is determined using the WAC method. The difference between the sales price and the cost, multiplied by the quantity (i.e., the shaded area between the sales and cost lines), represents the contribution margin.

The Reality Check

However, inventory cost represents the sum of expenses to obtain a specific batch of inventory. In reality, we have two sources of heat: internal heat from the production of Product 1 and heat from purchased gas.

Therefore, we essentially have two batches of finished goods with different costs:

- Product 2 produced without using natural gas.

- Product 2 produced using natural gas.

It does not matter how the cost of purchased gas is allocated in accounting. The key factor is that heat from Product 1 is always fully utilized, and producing every additional ton of Product 2 requires purchasing additional natural gas.

Let’s examine the sales plan when we separate the cost of products obtained without purchased gas from those using it in our accounting (Fig. 2).

The Illusion of Profitability

The Accounting View

The sales line is consistently above the cost line, meaning all sales are executed at a price higher than the reported cost. Consequently, the more we sell, the greater the profit. From an accounting perspective, everything seems correct.

The Reality View

However, the sum does not change if we rearrange the addends. Let’s swap the sales at maximum and minimum prices on the graph. We immediately see that a portion of sales is executed at prices lower than the specific variable cost of Product 2 produced with expensive gas (€650/ton).

This means that excluding these sales from the plan will actually increase our profit (see Fig. 3).

Key Conclusions from the Case Study

Based on this example, we can draw the following conclusions:

- Separate Costing: If different batches of raw materials with different prices are used to increase the production and sales volume of a single product type, then to maximize profit, it is necessary to separate the variable cost in accounting when using cheap and expensive raw materials. Then, compare the cost of the product made from expensive raw materials with the selling prices. If the variable cost of the product from expensive raw materials is higher than the minimum selling prices, such sales reduce total profit.

- Sales Planning Hierarchy: To maximize profit when planning sales for batches of a single product type, first plan to sell cheap batches of goods under contracts with maximum prices. Then, plan to sell the remaining batches only if the remaining contract prices exceed their specific variable cost.

The Financial Impact

At the real enterprise, this change in planning procedure generated about €500,000 per year in additional profit while reducing the quantity of products sold.

This logic is applicable not only to manufacturing but also to trading (retail/wholesale).

Summary

As we can see, using the Weighted Average Cost (WAC) method for inventory valuation in managerial accounting does not provide correct information for decision-making, even though WAC is permitted by current accounting standards (both national GAAP and IFRS).

We have already verified that in some cases, selling products at prices lower than the accounting cost can bring the enterprise additional profit – provided the selling price exceeds the variable cost. Conversely, in some cases, selling a product/good at a price higher than the reported cost can reduce the enterprise’s profit – when using weighted average cost for inventory valuation.

What’s Next?

However, the problem may not only be in using weighted average cost. If business constraints are not taken into account, other situations are possible where, by choosing a product with higher marginal profitability, we earn less profit than by choosing a product with a lower contribution margin per unit.

How is this possible? Read “Costing Traps (Part 3)“.

Comments are closed