Or Why Accounting Cost Is a Poor Criterion for Decision-Making.

Posted by Dmytro Dodenko

The main goal of any enterprise is to make as much money as possible, now and in the future. If an enterprise cannot earn enough money, the owners (shareholders) will try to invest their money in another enterprise that earns more. The primary indicator of a company’s success is profit—the amount by which revenues exceed expenses for the reporting period.

The Accounting Logic

Expenses are recognized in the Income Statement (P&L) based on the direct link between costs incurred and income earned under specific items (the Matching Principle). The profit of a manufacturing enterprise from its main activities is defined as revenue from product sales minus the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and minus other period expenses.

All enterprise costs associated with production are included in the cost of Finished Goods or Work in Progress (WIP) until the product is sold. At the time of sale, they are recognized as expenses and matched against sales revenue to calculate profit. Period costs are expenses not included in inventory valuation; therefore, they are treated as expenses falling within the period in which they were incurred.

Variable vs. Fixed Costs

Production costs can be variable or fixed (semi-fixed).

- Short-term variable costs change in direct proportion to the volume of production or level of activity (i.e., doubling activity leads to a doubling of variable costs). Thus, total variable costs are a linear function, while such costs per unit of output are constant.

- Fixed costs are costs incurred over a certain period that remain unchanged in magnitude over a wide range of production volumes (relevant range). Examples include depreciation of factory buildings, administrative salaries, equipment rent, heating costs, etc.

Variable costs per unit can be measured and matched directly. Fixed costs are attributed to the product cost by allocating them based on a selected allocation base (cost driver).

The Main Trap

If one evaluates the company’s performance guided solely by data from regulated financial accounting (absorption costing), which allocates both variable and fixed production costs to the product cost, one can reach erroneous conclusions. (For more details, see the note “When Accounting Can Deceive”).

Relevant Costs: The Decision-Making Standard

When making a decision, only those costs and revenues whose magnitude depends on the decision are significant.

- Such costs and revenues are called relevant (i.e., taken into account).

- Costs and revenues whose magnitude does not depend on the decision are irrelevant and should be ignored.

Thus, the relevant financial components analyzed in the decision-making process are future cash flows whose magnitude depends on the alternative options being considered. In other words, only incremental (differential) cash flows should be taken into account, while flows that remain unchanged under any scenario are irrelevant to the decision at hand.

Let’s look at specific examples:

Making Special Pricing Decisions

Occasionally, a company must make a decision regarding a transaction that falls outside its primary market scope.

For example, a company sells its products (pre-painted sheet metal) within Ukraine and exports to certain European countries. During a month of low demand, when the company has excess production capacity, it receives a request from a Belarusian* entity to sell 60 tons of painted metal at a price lower than the standard selling price and even below the production cost. The company has no prior sales history with Belarus, and there are currently no other orders from this country. However, according to the sales department, even a one-time sale would introduce consumers to the product quality and potentially allow for future market entry at standard prices. Should the company accept such an offer?

Read a detailed analysis of this case in my separate article: «Special Orders: Should You Accept a Price Below Production Cost?»

However, before making such a decision, it is crucial to consider a number of factors:

- Will selling at a lower price impact future market prices or relationships with existing customers?

- Will this order prevent the acceptance of more profitable proposals during the execution period?

- Is this the best utilization of the company’s spare resources?

When attempting to determine which costs are relevant for a specific decision, one may find that costs deemed relevant in one scenario become irrelevant in another.

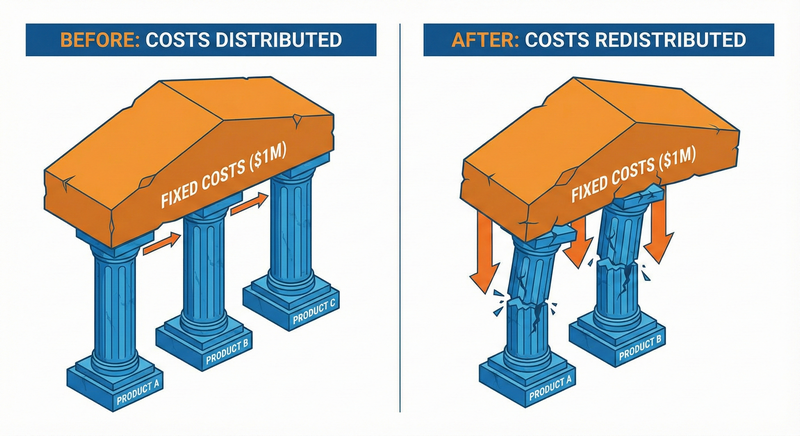

Decisions to Discontinue a Product Line (The Death Spiral)

A similar approach should be applied when deciding to discontinue the production of a specific product type.

Why removing a “loss-making” product from the portfolio can destroy a business: A story of failure.

Selling products at a price higher than cost increases profit, while selling below cost reduces it. This would seem to be an axiom. But is this always true in reality? Why can accounting cost be misleading? Let’s analyze a real-world case.

The Situation

A new executive was appointed to a company. He was young, educated, and ambitious. Determined to increase the company’s profits, he first requested data from the accountant regarding the production costs and selling prices of all manufactured products. The analysis revealed that some items were being sold at a price lower than their production cost. The executive ordered the discontinuation of these loss-making products.

Several months later, he repeated the analysis and discovered that other products had now become “unprofitable.” They were also removed from the product mix. Eventually, the company, which was once profitable, began to incur losses.

How did this happen?

The issue lies in the fact that accounting cost (fully absorbed cost) includes all expenses—both variable and fixed. When production volumes decreased, the total amount of fixed costs remained almost unchanged. However, these costs were now allocated across a smaller volume of products.

From an accounting perspective, the products were “loss-making,” but in reality, they were generating a contribution margin (the excess of the selling price over variable costs). When the products that covered a portion of the fixed costs were eliminated, those fixed costs were reallocated to the remaining products. Consequently, the margin generated by the remaining products was no longer sufficient to cover the total fixed costs. This case has become a “parable” in managerial accounting — a classic cost trap known as the “Death Spiral.”

Conclusion

Before closing a “loss-making” division or product line, analyze the following:

- What share of fixed costs does it cover?

- Are there alternatives to compensate for these costs?

- What impact will the decision have on other products?

Sometimes, “unprofitable” items are critical elements of the business model that support overall profitability.

Make-or-Buy Decisions: To Manufacture or Outsource?

To decide whether it is more profitable to manufacture a product (or component) internally or purchase it from an outside supplier, information about allocated fixed costs is irrelevant.

Relevant information includes:

- Variable production costs compared to the purchase price from a third-party manufacturer.

- The amount of income from the alternative use of the released production capacity (Opportunity Cost).

Також велике значення має інформація про те, чи є дана виробнича потужність обмеженням (вузьким місцем) для конкретного підприємства.

I have provided a detailed analysis of this mechanism and the algorithm for correct calculation in a separate article, “To produce or to buy? – How to avoid mistakes.”

I have provided a detailed analysis of this mechanism and the algorithm for correct calculation in a separate article «Make or Buy? How to Avoid Fatal Decisions».

Equipment Replacement Decisions: Ignoring Sunk Costs

Equipment replacement is a capital investment decision, meaning it is a long-term decision that requires the application of Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) procedures.

One aspect of asset replacement decisions involves the book value (historical cost less accumulated depreciation) of the old equipment. This issue often causes confusion.

The correct approach is based on applying relevant cost principles—recognizing that past or sunk costs are irrelevant to this decision. Only future cash flows associated with purchasing and using the new equipment are relevant. However, one must not forget about cash inflows from the possible sale of the old equipment (Salvage Value) or other alternative uses.

Summary

We have examined some aspects of information relevance for business decision-making and verified that in certain cases, selling products at prices lower than the accounting cost can bring the enterprise additional profit—provided the selling price exceeds the variable cost.

But in some cases, selling a product/good at a price higher than the cost can actually reduce the enterprise’s profit.

In which cases? Read «Costing Traps (Part 2)».